All of us have times of the day where we are operating on “autopilot.” We hop out of bed, go to the bathroom, brush our teeth, and groom ourselves for the day. Breakfast is usually the same every morning.

Even when we are driving, while listening to a song or news or just thinking about something, our brain can go on autopilot. Think of the times you’ve driven past your exit because you were thinking about something else. It can’t be just me!

Many times, we find ourselves on autopilot when it comes to tasks that we have been doing so long or which are repetitive. If we did not go on autopilot, we would be like our automatic nervous system and we would have to tell our heart when to beat and our lungs when to breath. However, when it comes to assessments, we tend to be keyed-in and are present and not on auto pilot because of the importance.

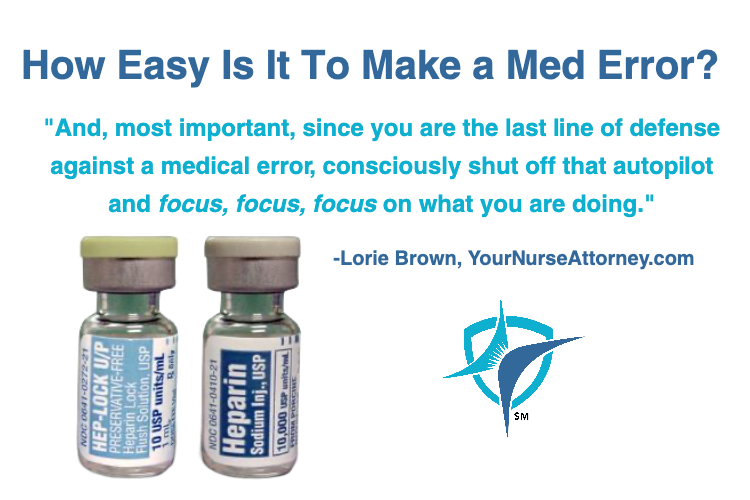

At Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis in 2006, NICU nurses caring for premature babies would retrieve heparin to administer to the babies when it was ordered. Tragically, the pharmacy technician had mistakenly stocked the medicine locker with dosages that were 1,000 times greater than what was required for the infants.

The treating nurses did not notice that the vial, labeled heparin instead of hep-lock, was a dark blue color rather than the baby blue of heparin. I can envision that they possibly may have been on autopilot and saw the first 3 letters, H-E-P, without realizing it was the adult dose of heparin rather than baby dose of heparin.

The mistake resulted in the deaths of 3 infants.

This is the same scenario with RaDonda Vaught at Vanderbilt Hospital of whom I have often written in the past. She mistakenly administered the strong paralytic vecuronium instead of the ordered Versed, resulting in the patient’s death. She was charged, tried, convicted, and sentenced for negligent homicide and abuse of a dependent adult. You can find more about this by reading previous articles archived in this blog.

As with the Methodist NICU nurses, Ms. Vaught may have been on autopilot, noticing the first few letters for both pharmaceutical (V-E) and tragically selected the incorrect one required for her patient.

Additionally, even speaking the names of some medicines that sound alike while on autopilot can also lead to a selection error.

When vials look so similar, have names that look and sound similar, it is easy to get them mixed up and possibly result in injury or, as in the Vaught matter, even death!

I do not need to emphasize that it is imperative for pharmaceutical companies to do what they can to differentiate the various medications by their labels, their packaging or even by their names [examples]. It goes without saying that the better the medicines are differentiated, the less likely a mishap will happen.

And, most important, since you are the last line of defense against a medical error, consciously shut off that autopilot and focus, focus, focus on what you are doing!

Leave a Reply